19 January 2006: Thursday of the 2nd Week in Ordinary Time

Mark 3, 7-12: The hungry crowd

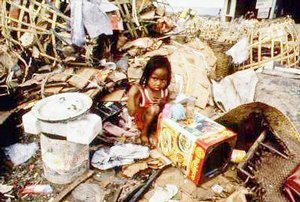

The Gospel that we heard today is a very familiar scene. Jesus leaves the synagogue, away from his detractors, and then discovers Himself in a place teeming with hungry people--- not just of those who are physically hungry, but those who are in great need--- the sick, the suffering, the demon-possessed, those who are hungry for spiritual matters. Indeed, people without a shepherd.

As I prayed over this passage today, I find myself like all of these people hungry for Jesus, in great need of God. I was not like his disciples who are always with Him. You may be very surprised because priests are supposed to be closest to Jesus, using the real meaning of what the unclean spirits were shouting: the sons of God. You see, in the ancient times, sons of God literally mean those who are close to God. In Genesis and the book of Job, they are the angels; In Exodus and Hosea, the chosen nation, Israel, is regarded as the son of God (“Israel is my first-born son” Ex 4, 22); In 2 Samuel 7, 14, the king is the son of God (“I will be His father, and he will be my son.”); and in the later books like Sirach, the good man is the son of God. Anyone who is especially near and close to God is a “son”. In the New Testament, Paul calls Timothy, who is not his biological son, as “son” because Timothy knew his mind. Peter also calls Mark, his son, because no one can interpret his mind so well. Priests are supposed to be especially close to God, because I am suppose to know in some way the mind of God as Timothy is to Paul, and Mark is to Peter; I am supposed to explain what God has to say for us now. And yet, I find myself in prayer like those who are in great need to God.

Jesus promised that if we have the purity of heart, we shall see God. What, exactly, blocks this purity of heart? Why do we so often confuse the experience of God with our own projects and self-interests? Especially for many religious who have often rationalized, “my work is my prayer” or “every thing anyway is for God”.

In the birth of philosophy, ancient

This image explains to us, as Freud explains, why there is much emptiness in our hearts. We are obsessed with ourselves. Just observe how many times we use the pronoun I, me, and myself. Just tally how many times we say declarations like this, “This is my life, this is my love”, “Why are you concerned about my life. Rene Descartes searched for the indubitable starting point for his philosophy, and until he came to a reality that he could not doubt: “I think, therefore, I am!” In Descartes’ mind, what we can be sure of, what we know is real, is ourselves. Descartes’ philosophy lives in us when we say, “I think, therefore, I am... my heartaches, my headaches, my problems, my wounds, my financial shortages, my grades, my achievements, my tasks, my worries are all real. Other people’s lives and the larger community and its concerns are not as real.” And thus, many of our lives are hooked into our own pursuits of excellence, material comfort, and hunger to come up the ladder of success. And we find ourselves hungry than ever, empty than ever. There is a pining loneliness in us that we seek to find happiness in fleeting enjoyments and pleasures. And thus, born to this generation, I and all of us are all seeking for Jesus. We pray that Jesus may heal us of our narcissism.

No comments:

Post a Comment